Hands-on data visualization using p5

This is a p5 (http://p5js.org) version of the Processing tutorial that I published earlier. P5 is a javascript version of the very popular Processing tool. This tutorial holds numerous code snippets that can by copy/pasted and modified for your own purpose. The contents of this tutorial is available under the CC-BY license.

The tutorial is written in a very incremental way. We start with something simple, and gradually add little bits and pieces that allow us to make more complex visualizations. So make sure to not skip parts of the tutorial: everything depends on everything that precedes it.

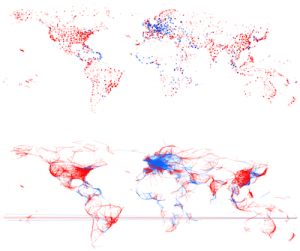

Figure 1 - A pretty picture

Introduction to P5

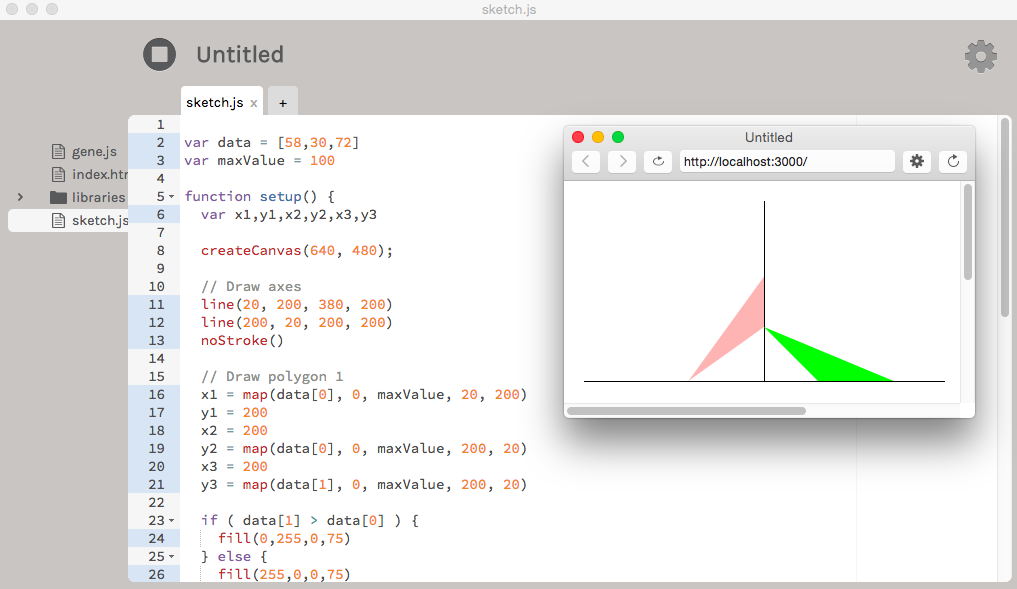

P5 is a language based on javascript. You can either use its own development environment, or load is as a dependency in your own scripts.

Figure 2 - The P5 IDE

Download and install the p5 development environment

We’ll make things easy and just use the P5 integrated development environment. Download it from http://p5js.org/download/. There are Mac and Windows versions available.

UPDATE 2018: The IDE mentioned here to download has been deprecated and is no longer supported. A webinterface has been released to replace this, at http://editor.p5js.org. Another user interface is available at http://www.openprocessing.org which is geared towards e.g. creating scripts for courses etc.

A minimal script

A minimal script is provided below.

Script 1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

function setup() {

createCanvas(400,400)

fill(255,0,0)

ellipse(100,150,20,20)

fill(0,255,0)

rect(200,200,50,60)

stroke(0,0,255)

strokeWeight(5)

line(150,5,150,50)

}

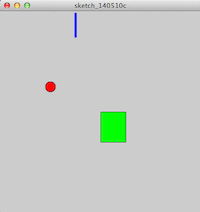

This code generates the following image:

Figure 3 - Minimal output

The numbers at the front of each line are the line numbers and are actually not part of the program. We’ve added them here to be able to refer to specific lines. So if you type in this piece of code, do not type the line numbers.

Let’s walk through each line. First of all, the script needs to be wrapped in a function named setup(). Within this function, the actual code is made up of a list of statements. The first line in the script createCanvas(400,400) sets the dimensions of the resulting image. In this case, we’ll generate a picture of 400x400 pixels.

Next, (line [4]) we set the colour of anything we draw to red. The fill function takes 3 parameters, which are the values for red, green, and blue (RGB), ranging from 0 to 255. We then draw an ellipse with its center at horizontal position 100 pixels and vertical position 150 pixels. Note that the vertical position counts from the top down instead of from the bottom up. The point (0,0) is at the top left rather than the bottom left… For the ellipse we set both the horizontal and vertical diameter to 20 pixels, which results in a circle.

The next thing we do (line [7]) is set the colour of anything that we will draw to green fill(0,255,0), and draw a rectangle at position (200,200) with width set to 50 and height to 60.

Finally, we set the colour of lines to blue (stroke(0,0,255)), the stroke weight to 5 pixels strokeWeight(5), and draw a line line(150,5,150,50). This line runs from point (150,5) to (150,50).

Both fill and stroke are used to set colour: fill to set the colour of the shape, stroke to set the colour of the border around that shape. In case of lines, only the stroke colour can be set.

Several drawing primitives exist, including line, rect, triangle, and ellipse (a circle is an ellipse with the same horizontal and vertical radius). A treasure trove of information for these is available in the P5 reference pages.

Apart from these primitives, P5 contains functions that modify properties of these primitives. These include setting the fill color (fill), color of lines (stroke), and line weight (lineWeight). Again, the reference pages host all information.

Variables, loops and conditionals

What if we want to do something multiple times? Suppose we want to draw 10 lines underneath each other. We could do that like this:

Script 2

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

function setup() {

createCanvas(500,150)

background(255,255,255)

line(100,0,400,0)

line(100,10,400,10)

line(100,20,400,20)

line(100,30,400,30)

line(100,40,400,40)

line(100,50,400,50)

line(100,60,400,60)

line(100,70,400,70)

line(100,80,400,80)

line(100,90,400,90)

}

This generates this image:

Figure 4 - Parallel lines

Of course this is not ideal: what if we have 5,000 datapoints to plot? To handle real data, we will need variables, loops, and conditionals.

In the code block above, we can replace the hard-coded numbers with variables. These can be integers, floats, strings, arrays, etc. startX = 100 creates a new variable called startX and gives it the value of 100.

Script 3

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

function setup() {

createCanvas(500,150)

startX = 100

stopX = 400

background(255,255,255);

for (var i = 0; i < 10; i++ ) {

line(startX,i*10,stopX,i*10)

}

}

We first set the variables startX and stopX to 100 and 400. We then loop over values i, which starts at 0 and increases in each loop as long as i is smaller than 10. In each loop, a line is drawn.

We can use conditionals to for example distinguish odd or even lines by colour.

Script 4

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

function setup() {

createCanvas(500,150);

var startX = 100;

var stopX = 400;

background(255,255,255);

strokeWeight(2);

for ( var i = 0; i < 10; i++ ) {

if ( i%2 == 0 ) {

stroke(255,0,0);

} else {

stroke(0,0,255);

}

line(startX,i*10,stopX,i*10);

}

}

In this code snippet, we check in each loop if i is even or odd, and let the stroke colour depend on that result. An if-clause has the following form:

if ( *condition* ) {

// do something

} else {

// do something else

}The condition i%2 == 0 means: does dividing the number i with 2 result in a remainder of zero? Note that we have to use 2 equal-signs here (==) instead of just one (=). This is so to distinguish between a test for equality, and an assignment. Don’t make errors against this…

Figure 5 - Odd and even lines

Exercise data

The data for this exercise can be downloaded here and concerns flight information between different cities. Each entry in the dataset contains the following fields:

- from_airport

- from_city

- from_country

- from_long

- from_lat

- to_airport

- to_city

- to_country

- to_long

- to_lat

- airline

- airline_country

- distance

Installing P5 as a library

Although it is possible to load data files into the openprocessing environment, you cannot do so when using the P5 online editor at editor.p5js.org. Also, the space you get in openprocessing is limited, so when doing any real P5 development, it makes sense to install it as a library and run a local web server. For more information, see http://p5js.org/get-started/. The description below is the quickest way to get you going; not necessarily the best long-term solution. For that, look into bower, for example.

Getting the library

Download “p5.js complete” from http://p5js.org/download/ onto your computer and unzip.

Setting up your files

You will need 2 files to get going: index.html and script.js. Put these files in the directory that you just unzipped.

index.html should look like this:

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<script language="javascript" type="text/javascript" src="p5.js"></script>

<script language="javascript" type="text/javascript" src="sketch.js"></script>

<!-- this line removes any default padding and style. you might only need one of these values set. -->

<style> body {padding: 0; margin: 0;} </style>

</head>

<body>

</body>

</html>script.js would be the script that you put into the editor like before, for example:

function setup() {

createCanvas(400,400)

fill(255,0,0)

ellipse(100,150,20,20)

fill(0,255,0)

rect(200,200,50,60)

stroke(0,0,255)

strokeWeight(5)

line(150,5,150,50)

}Do not use Microsoft Word for this! Code editors include atom, Sublime Text, TextMate or just Notepad if you’re on Windows.

Running a webserver

So how do you “run” this visualization? You do this by running a local webserver. Depending on your operating system, there are several options for this. Getting these installed is not within the scope of this tutorial. In short, if you have python installed, type in python -m SimpleHTTPServer on the command line in the directory with the p5.js, index.html and script.js files. When that’s done, open your web browser and go the http://localhost:8000. If your script.js looks like the one above, you should see three objects in your browser: a circle, a rectangle, and a line.

If you need help setting up the webserver, check out https://github.com/processing/p5.js/wiki/Local-server.

Inspector

TODO

Using the file in P5

Let’s write a small script in P5 to visualize this data. The visual encoding that we’ll use for each flight will be the following:

- x position is defined by longitude of departure airport

- y position is defined by latitude of departure airport

Script 5

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

var table;

function preload() {

table = loadTable("flights.csv","csv","header")

}

function setup() {

createCanvas(600,300)

noStroke()

fill(0,0,255,10)

background(255,255,255)

var rows = table.getRows()

for (var r = 0; r < rows.length; r++) {

var from_long = rows[r].getNum("from_long")

var from_lat = rows[r].getNum("from_lat")

var x = map(from_long,-180,180,0,width)

var y = map(from_lat,-90,90,height,0)

ellipse(x,y,3,3)

}

}

The resulting image:

Figure 6 - Departure airports

You can see that the resulting image shows a map of the world, with areas with high airport density clearly visible. Notice that the data itself does not contain any information where the continents, oceans and coasts are; still, these are clearly visible in the image.

Let’s go through the code:

- [1] We create a variable

tableto hold all information from the file. This variable needs to be defined outside of thepreloadandsetupfunctions, because it is a global variable: it should be available to all functions, not just within a specific one. - [3-5] The

preloadfunction loads the data from the file into thetablevariable. The"header"indicates that the first line of the file is a list of column headers. Why don’t we just load the data within thesetupfunction? That’s because javascript works asynchronously which means that it will not wait to run the rest of the script until all data is loaded. Usingpreload, thesetupfunction will only run when all data is loaded. - [8]

noStroke()tells P5 to not draw the border around disks, rectangles or other elements. - [12] We load all rows from the file into an array.

- [13-19] Each element of the array represents a single flight. Here, we will draw a blue circle for each of them.

- [14] For the

r-th row, we get the element in thefrom_longcolumn. As this is a number, we get it using the.getNummethod. If we needed it as a string, we’d use.getString. - [16] In this line, we transform the longitude value to a value between 0 and the width of our canvas.

The map function is very useful. It is used to rescale values. In our case, longitude values range from -180 to 180. The x position of the dots on the screen, however, have to be between 0 and 800 (because that’s the width of our canvas, as set in createCanvas(800,400);). In this case, we can even use the variable width instead of 800, because width and height are set automatically when we call the statement createCanvas(800,400);. The y position input range is [-90,90] instead of [-180,180], which is reflected in line 17.

You see that the map function for y recalculates the from_lat value to something between height and 0, instead of between 0 and height. The reason is that the origin of our canvas is at the top-left corner instead of the bottom-left one so we have to flip coordinates.

We can add additional information to this visualization. In the next code block, we alter our script so that colour of the dots is red for domestic flights and blue for international flights. In addition, the size of the dots is proportional to the distance of that particular flight.

Script 6

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

var table;

function preload() {

table = loadTable("flights.csv","csv","header")

}

function setup() {

createCanvas(600,300)

noStroke()

fill(0,0,255,10)

background(255,255,255)

var rows = table.getRows()

for (var r = 0; r < rows.length; r++) {

var from_long = rows[r].getNum("from_long")

var from_lat = rows[r].getNum("from_lat")

var from_country = rows[r].getString("from_country")

var to_country = rows[r].getString("to_country")

var distance = rows[r].getNum("distance")

var x = map(from_long,-180,180,0,width)

var y = map(from_lat,-90,90,height,0)

if ( from_country == to_country ) {

fill(255,0,0,10)

} else {

fill(0,0,255,10)

}

var radius = map(distance,1,15406,3,15)

ellipse(x,y,radius,radius)

}

}

In line [27], we rescale the value of the distance (min = 1, max = 15406) to a minimum of 3 and maximum of 15. That value is than used as the radius.

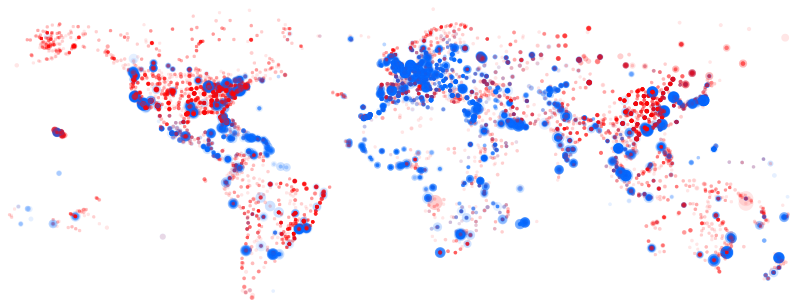

Figure 7 - Domestic vs international flights

From this picture, we can deduce many things:

- Airports tend to be located on land => plotting latitude and longitude recreates a worldmap.

- Blue international flights tend to depart from coastal regions.

- There are few domestic flights within Europe.

- Longer flights (departure airports with larger radius) tend to leave in coastal regions

Interactivity and defining functions

It is often the interactivity in data visualization that helps gaining insights in that data and finding new hypotheses. Up until now, we have generated static images. How can we add interactivity?

As a first use case, say that we want the radius of the dots to depend on the position of the mouse instead of the distance of the flight: if our mouse is at the left of the image, all dots should be small; if it is at the right, they should be large. We will change the line var radius = map(distance,1,15406,3,15); to include information on the mouse position.

This time, instead of creating a simple image, this image will have to be redrawn constantly taking into account the mouse position. For this, we have to rearrange our code a little bit. Some of the code has to run only once to initialize the visualization, while the rest of the code has to be rerun constantly. We do this by putting the code that we have either in the setup() or the draw() function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

// define global variables here

function setup() {

// code that has to be run only once

}

function draw() {

// code that has to be rerun constantly

}

A function definition (such as setup and draw) in javascript always has the same elements:

- The

functionkeyword - The name of the function

- The names of parameters, between parentheses

- The actual code of the function, between curly brackets

Both the setup() and the draw() functions don’t take any parameters, so we just use empty parentheses.

The setup() function is only run once; the draw() function is run by default 60 times per second. Until now, we have only used the setup() function because we only wanted a static image. But if we want to redraw the image, there are still some parts that need only be done once.

Let’s move the statements needed for redrawing into the draw() function:

Script 7

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

var table;

function preload() {

table = loadTable("flights.csv","csv","header")

}

function setup() {

createCanvas(600,300)

noStroke()

}

function draw() {

background(255,255,255)

var rows = table.getRows()

for (var r = 0; r < rows.length; r++) {

var from_long = rows[r].getNum("from_long")

var from_lat = rows[r].getNum("from_lat")

var from_country = rows[r].getString("from_country")

var to_country = rows[r].getString("to_country")

var distance = rows[r].getNum("distance")

var x = map(from_long,-180,180,0,width)

var y = map(from_lat,-90,90,height,0)

if ( from_country == to_country ) {

fill(255,0,0,10)

} else {

fill(0,0,255,10)

}

var radius = map(distance,1,15406,3,15)

ellipse(x,y,radius,radius)

}

}

The draw() function is run 60 times per second. This means that 60 times per second each line in the input table is processed again to draw a new circle. As this is quite compute intensive, your computer might actually not be able to redraw 60 times per second, and show some lagging. For simplicity’s sake, we will however not go into optimization here.

Note that we have to set the background every single redraw. If we wouldn’t, each picture is drawn on top of the previous one.

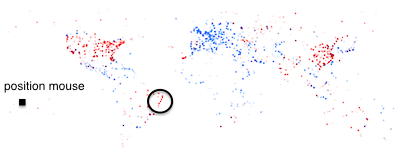

Now how do we adapt this so that the radius of the circles depends on the x-position of my pointer? Luckily, P5 provides two variables called mouseX and mouseY that are very useful. mouseX returns the x position of the pointer. So basically the only thing we have to do is replace var radius = map(distance, 0, 15406, 3, 15); with var radius = map(mouseX, 0, 800, 3, 15); (Note that we changed the 15406 to 800.) If we do that, and our mouse is towards the right side of the image, we get the following picture:

Figure 8 - Large dots

Here’s the interactive version (move your mouse across the picture):

Some optimization

Let’s optimize this code a tiny bit. We could for example remove the lines that handle the distance because we don’t use them. However, we’ll leave those in because we’ll use them in the next example…

You’ll notice that the picture is not that responsive: you have to wait a bit before it is refreshed. This is because it reparses the input every single time that it wants to redraw. The obvious way to solve this is to put that information in memory, but we’ll look into that (using objects) later.

Something else that we can do is limit the number of times the picture is redrawn. As long as I don’t move my mouse I don’t have to redraw the picture. To do that, we add noLoop(); to the setup() function, and add a new function at the bottom, called mouseMoved(). In this new function, we tell P5 to redraw() the canvas. The resulting code looks like this:

Script 8

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

var table;

function preload() {

table = loadTable("flights.csv","csv","header")

}

function setup() {

createCanvas(600,300)

noStroke()

noLoop()

}

function draw() {

background(255,255,255)

var rows = table.getRows()

for (var r = 0; r < rows.length; r++) {

var from_long = rows[r].getNum("from_long")

var from_lat = rows[r].getNum("from_lat")

var from_country = rows[r].getString("from_country")

var to_country = rows[r].getString("to_country")

var distance = rows[r].getNum("distance")

var x = map(from_long,-180,180,0,width)

var y = map(from_lat,-90,90,height,0)

if ( from_country == to_country ) {

fill(255,0,0,10)

} else {

fill(0,0,255,10)

}

var radius = map(mouseX, 0, 800, 3, 15)

ellipse(x,y,radius,radius)

}

}

function mouseMoved() {

redraw()

return false

}

Note the return false at the end of the mouseMoved() function. From the P5 reference documentation for that method: “Browsers may have different default behaviors attached to various mouse events. To prevent any default behavior for this event, add return false to the end of the method.”

More useful interactivity

This interactivity can be made more useful: we can use the mouse pointer as a filter. For example: if our mouse is at the left only short distance flights are drawn; if our mouse is at the right only long distance flights are drawn.

Script 9

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

var table;

function preload() {

table = loadTable("flights.csv","csv","header")

}

function setup() {

createCanvas(600,300)

noStroke()

noLoop()

}

function draw() {

background(255,255,255)

var rows = table.getRows()

for (var r = 0; r < rows.length; r++) {

var distance = rows[r].getNum("distance")

var mouseXMin = mouseX - 25

var mouseXMax = mouseX + 25

var minDistance = map(mouseXMin,0,800,0,15406)

var maxDistance = map(mouseXMax,0,800,0,15406)

if ( minDistance < distance && distance < maxDistance ) {

var from_long = rows[r].getNum("from_long")

var from_lat = rows[r].getNum("from_lat")

var from_country = rows[r].getString("from_country")

var to_country = rows[r].getString("to_country")

var distance = rows[r].getNum("distance")

var x = map(from_long,-180,180,0,width)

var y = map(from_lat,-90,90,height,0)

if ( from_country == to_country ) {

fill(255,0,0,10)

} else {

fill(0,0,255,10)

}

ellipse(x,y,5,5)

}

}

}

function mouseMoved() {

redraw()

return false

}

We will only draw flights if their duration is between a calculated minDistance and maxDistance. That’s what we do on line [22]. Of course we first have to calculate minDistance and maxDistance. That’s what we do on lines [17] to [20]. In lines [17] and [18], we say that we will be looking 25 pixels at either side of the mouse position. If the pointer is at position 175, mouseMin is set to 150 and mouseMax to 200. This pixelrange is then translated into distance range on lines [19] and [20].

Now it gets interesting. We can now look a bit deeper into the data… If we have our mouse at the left side of the image, it looks like this:

Figure 9 - Short distance flights

Having the mouse in the middle to the canvas gives us this image:

Figure 10 - Medium distance flights

Here’s an interactive version (move your mouse across the picture):

Playing with this visualization, there are some signals that pop up. Moving left and right at about 70-90 pixels from the left, we see a “snake” moving along the north-east coast of Brazil (see Figure below, also indicating position of mouse). This indicates that most of these flights probably go to the same major city in that country. Other dynamic patterns appear in Europe as well. In Figure 10, some dots appear to be darker than others. Why do you think this is?

Figure 11 - A snake in Brazil

Brushing and linking

Very often, you will want to create views that show different aspects of the same data. In our flights case, we might want to have both a map and a histogram of the flight distances. To be able to do this, we will have to look at how to create objects.

Working with objects

Dogs

The code that we have been writing so far is what they call “imperative”: the code does not know what we are talking about (i.e. flight data); it just performs a single action for each line in the file. As a result, all things (dots) on the screen are completely independent. They do not know of each other’s existence. To create linked views, however, we will need to make these visuals more self-aware, which we do by working with objects. Objects are members of a specific class. For example, Rusty, Duke and Lucy are three dogs; in object-oriented speak, we say that Rusty, Duke and Lucy are “objects” of the “class” dog. Of course, all dogs have types of properties in common: they have names, have a breed, a weight, etc. At the same time, they share some methods, for example: they can all bark, eat, pee, …

In object-oriented programming, we first define classes that completely describe the properties and methods of that type of object. Have a look at this bit of code that defines and creates a dog. Here we do something similar.

Script 10

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

var dog1, dog2;

var dog = function(n,b,w) {

this.name = n

this.breed = b

this.weight = w

this.bark = function() {

println("My name is " + this.name + ", I'm a " + this.breed + ", and I weigh " + this.weight + " kg")

}

this.eat = function() {

println("I am " + this.name + " and I ate")

}

this.pee = function() {

println("I am " + this.name + " and I've got wet legs now...")

}

};

function setup() {

createCanvas(710, 400);

dog1 = new dog("Buddy", "Rottweiler", 19);

dog2 = new dog("Lucy","Terrier",8)

dog1.bark()

dog1.eat()

dog1.pee()

dog2.bark()

dog2.eat()

dog2.pee()

}

When you run this code, you will see an empty picture (because we didn’t draw anything), but you will also see some text appear in the black terminal underneath your code. That text should be:

My name is Buddy, I'm a Rottweiler, and I weight 19 kg I am Buddy and I ate I am Buddy and I've got wet legs now My name is Lucy, I'm a Terrier, and I weight 8 kg I am Lucy and I ate I am Lucy and I've got wet legs now

So what did we do? Outside of the setup() method, in lines 3 to 19, we defined a new object prototype, called dog. To all extent and purposes for this tutorial, an object prototype in javascript is the same as a class in any other language (Java, python, etc). In such prototype, we want to do 2 things: (1) set the properties of the object (lines 4 to 6), and (2) define any methods of the class (lines 8 to 18).

In our little example here, the methods bark(), eat() and pee() don’t do anything else than sending some text to the console, using println().

Now what does this actually mean? We can create new objects just like we create variables before, for example the startX = 100 in script 4. Just like we did in the previous scripts, we create 2 new variables (of the type dog).

var dog1 = new dog("Buddy","Rottweiler",19)Once we have these objects, we can call the methods on them that we defined in the class definition, as is shown in lines 27 to 32.

One flight

So what could a flight class look like? Let’s alter this code so that we use a Flight class.

Script 13

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

var my_flight;

var flight = function(d,flo,fla,tlo,tla,fc,tc) {

this.distance = d

this.from_long = flo

this.from_lat = fla

this.to_long = tlo

this.to_lat = tla

this.from_country = fc

this.to_country = tc

this.departureX = map(this.from_long, -180,180,0,width)

this.departureY = map(this.from_lat, -90,90,height,0)

this.drawDepartureAirport = function() {

ellipse(this.departureX, this.departureY, 5,5)

}

}

function setup() {

createCanvas(800, 400);

noStroke()

fill(255,0,0,50)

my_flight = new flight(1458, 61.838, 55.509, 38.51, 55.681, "Belgium", "Germany")

}

function draw() {

background(255,255,255)

my_flight.drawDepartureAirport()

}

For simplicity’s sake, we only draw a single flight in this example. So what did we do? First we create a global variable my_flight, which we will use in the setup() and draw() functions. Next, we define the flight class in lines 3 to 19. We start out with getting all parameters that we will give later (see line 24), and putting those in properties of the object. We also already calculate the x and y positions of the departure airport, because this will not change during the run of the program. Finally, we create the function to actually draw the departure airport of the flight on the screen. This just involves creating an ellipse.

In the setup() method, we create a new object/variable of the class flight, and assign it to the variable my_flight. Next, in the draw() method, we actually draw the flight (line 29). Notice here that we don’t write ellipse() or anything drawing-specific here. We write my_flight.draw() because any flight object knows how to draw itself. The drawDepartureAirport() method definition on lines 15 to 17 returns an ellipse whenever that method is called.

Many flights

In the code of script 13, we only drew one flight. Here is the same code as in script 13, but showing all flights.

Script 14

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

var table;

var flights = [];

var flight = function(d,flo,fla,tlo,tla,fc,tc) {

this.distance = d

this.from_long = flo

this.from_lat = fla

this.to_long = tlo

this.to_lat = tla

this.from_country = fc

this.to_country = tc

this.departureX = map(this.from_long, -180,180,0,width)

this.departureY = map(this.from_lat, -90,90,height,0)

this.drawDepartureAirport = function() {

ellipse(this.departureX, this.departureY, 5,5)

}

}

function preload() {

table = loadTable("flights.csv","csv","header")

}

function setup() {

createCanvas(800, 400);

noStroke()

noLoop()

fill(255,0,0,50)

var rows = table.getRows()

for ( var i in rows ) {

var from_airport = rows[i].getString("from_airport")

var from_city = rows[i].getString("from_city")

var from_country = rows[i].getString("from_country")

var from_long = rows[i].getNum("from_long")

var from_lat = rows[i].getNum("from_lat")

var to_airport = rows[i].getString("to_airport")

var to_city = rows[i].getString("to_city")

var to_country = rows[i].getString("to_country")

var to_long = rows[i].getNum("to_long")

var to_lat = rows[i].getNum("to_lat")

var airline = rows[i].getString("airline")

var airline_country = rows[i].getString("airline_country")

var distance = rows[i].getNum("distance")

var this_flight = new flight(distance, from_long, from_lat, to_long, to_lat, from_country, to_country)

flights.push(this_flight)

}

}

function draw() {

background(255,255,255)

for ( var i in flights ) {

flights[i].drawDepartureAirport()

}

}

As always, let’s see what is different in this script relative to the previous one. For starters, the flight class/prototype is exactly the same as in script 13. Some parts are the same as in script 11, before we started working with these object things. But these are the really new things:

- On line 2, we define a global variable

flightsand make it an empty array. Why can we not just declare it just likevar tableon line 1? Because we will apply an array-specific function on line 34 before the array contains any elements. - Lines 33 and 55 show a different way to loop over the elements of an array than we saw before. The command

for ( var i in rows ) {}does exactly the same as how we looped over arrays previously: it increasesiwith one for every loop. - On line 34 to 49, we go over each line in the file, get the required columns for that row, and create a new flight object. We then add (

push) that new flight to theflightsarray (line 49). - On lines 55 to 57, we loop over all flights and let each draw itself.

The resulting picture should be the same as that from script 5 (i.e. Figure 6).

Linking two copies of the departure plots

Now that we work with objects, we can start implementing brushing and linking. Let’s first look at the brushing.

Brushing

Let’s change the code from script 14 a bit, so that all objects that are in the vicinity (e.g. within 10 pixels) of the mouse position are “active”. To do this, we’ll (1) add a new function to the Flight class, which checks if an object (i.e. flight) is selected/activated or not, and (2) change the drawDepartureAiport() function a bit to distinguish between selected and non-selected objects.

Add the following function to the Flight class:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

this.selected = function() {

if ( dist(mouseX, mouseY, this.departureX, this.departureY) < 10 ) {

return true

} else {

return false

}

}

And change the drawDepartureAiport() function to this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

this.drawDepartureAirport = function() {

if ( this.selected() ) {

fill(255,0,0,25)

} else {

fill(0,0,255,10)

}

ellipse(this.departureX, this.departureY, 5,5)

}

You’ll also have to either remove the noLoop() from the setup() method, or add a void mouseMoved() method just like in script 8. (Hint: the section option is better…)

The selected() function returns either true or false for a given flight, depending on the mouse position. We can then use that result in the drawDepartureAiport() function: if ( this.selected() ) {}.

Your resulting code will look like script 15 below. All airports will be in blue, except the ones in the vicinity of the mouse position which will be red.

Script 15

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

var table;

var flights = [];

var flight = function(d,flo,fla,tlo,tla,fc,tc) {

this.distance = d

this.from_long = flo

this.from_lat = fla

this.to_long = tlo

this.to_lat = tla

this.from_country = fc

this.to_country = tc

this.departureX = map(this.from_long, -180,180,0,width)

this.departureY = map(this.from_lat, -90,90,height,0)

this.selected = function() {

if ( dist(mouseX, mouseY, this.departureX, this.departureY) < 10 ) {

return true

} else {

return false

}

}

this.drawDepartureAirport = function() {

if ( this.selected() ) {

fill(255,0,0,25)

} else {

fill(0,0,255,10)

}

ellipse(this.departureX, this.departureY, 5,5)

}

}

function preload() {

table = loadTable("flights.csv","csv","header")

}

function setup() {

createCanvas(800, 400);

noStroke()

noLoop()

var rows = table.getRows()

for ( var i in rows ) {

var from_airport = rows[i].getString("from_airport")

var from_city = rows[i].getString("from_city")

var from_country = rows[i].getString("from_country")

var from_long = rows[i].getNum("from_long")

var from_lat = rows[i].getNum("from_lat")

var to_airport = rows[i].getString("to_airport")

var to_city = rows[i].getString("to_city")

var to_country = rows[i].getString("to_country")

var to_long = rows[i].getNum("to_long")

var to_lat = rows[i].getNum("to_lat")

var airline = rows[i].getString("airline")

var airline_country = rows[i].getString("airline_country")

var distance = rows[i].getNum("distance")

var this_flight = new flight(distance, from_long, from_lat, to_long, to_lat, from_country, to_country)

flights.push(this_flight)

}

}

function draw() {

background(255,255,255)

for ( var i in flights ) {

flights[i].drawDepartureAirport()

}

}

function mouseMoved() {

redraw()

}

Linking

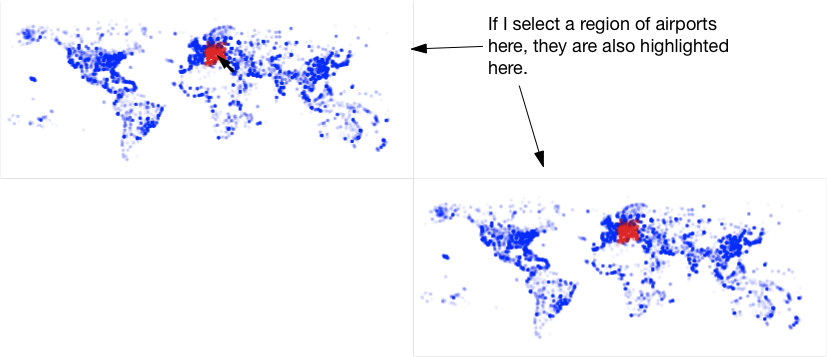

Now that we have the brushing working, let’s create a proof of principle for the linking. To make this work, we’ll first use a rather useless example, where we draw not one, but two maps of the world. But brushing airports in the first map will highlight them in the second map. We’ll make the map a quarter of the size by only using half of the width and half of the height for each. What will we have to change relative to script 15?

- The calculation of

yfor each airport will have to be changed. Instead of just creating just one x and y for a flight, we now need two:x1,y1, andx2,y2. As the two maps will be one above the other,x1andx2will be the same. The values fory1andy2however differ. The map function should now not rescale the values fory1from -180 and 180 to0andheight, but from0toheight/2. The values fory2can then range fromheight/2toheight. - The

drawDepartureAiport()function will draw each airport twice. Once usingx1andy1, and once usingx2andy2.

So we get the code like this:

Script 16

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

var table;

var flights = [];

var flight = function(d,flo,fla,tlo,tla,fc,tc) {

this.distance = d

this.from_long = flo

this.from_lat = fla

this.to_long = tlo

this.to_lat = tla

this.from_country = fc

this.to_country = tc

this.departureX = map(this.from_long, -180,180,0,width)

this.departureY = map(this.from_lat, -90,90,height/2,0)

this.arrivalX = map(this.from_long, -180,180,0,width)

this.arrivalY = map(this.from_lat, -90,90,height,height/2)

this.selected = function() {

if ( dist(mouseX, mouseY, this.departureX, this.departureY) < 10 ) {

return true

} else {

return false

}

}

this.drawDepartureAirport = function() {

if ( this.selected() ) {

fill(255,0,0,25)

} else {

fill(0,0,255,10)

}

ellipse(this.departureX, this.departureY, 5,5)

ellipse(this.arrivalX, this.arrivalY, 5,5)

}

}

function preload() {

table = loadTable("flights.csv","csv","header")

}

function setup() {

createCanvas(800, 800);

noStroke()

noLoop()

var rows = table.getRows()

for ( var i in rows ) {

var from_airport = rows[i].getString("from_airport")

var from_city = rows[i].getString("from_city")

var from_country = rows[i].getString("from_country")

var from_long = rows[i].getNum("from_long")

var from_lat = rows[i].getNum("from_lat")

var to_airport = rows[i].getString("to_airport")

var to_city = rows[i].getString("to_city")

var to_country = rows[i].getString("to_country")

var to_long = rows[i].getNum("to_long")

var to_lat = rows[i].getNum("to_lat")

var airline = rows[i].getString("airline")

var airline_country = rows[i].getString("airline_country")

var distance = rows[i].getNum("distance")

var this_flight = new flight(distance, from_long, from_lat, to_long, to_lat, from_country, to_country)

flights.push(this_flight)

}

}

function draw() {

background(255,255,255)

for ( var i in flights ) {

flights[i].drawDepartureAirport()

}

}

function mouseMoved() {

redraw()

}

The lines in the code that have changed relative to script 15 are: lines 15 and 16, and line 33. We also make the picture 800 pixels high instead of 400 (line 49). You should see an image similar to this (without the annotated text):

Figure 12 - Brushing and linking

Linking departure to arrival airports

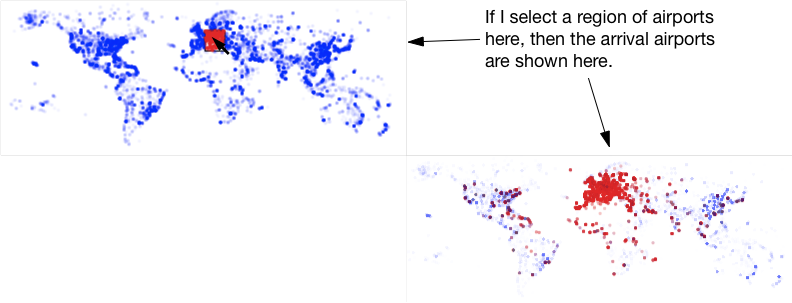

This visualization is not really useful. But how about we draw the departure airport in the top, and the arrival airport in the bottom. Brushing a group of departure airports in the top would then highlight the arrival airports in the bottom.

Script 17

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

var table;

var flights = [];

var flight = function(d,flo,fla,tlo,tla,fc,tc) {

this.distance = d

this.from_long = flo

this.from_lat = fla

this.to_long = tlo

this.to_lat = tla

this.from_country = fc

this.to_country = tc

this.departureX = map(this.from_long, -180,180,0,width)

this.departureY = map(this.from_lat, -90,90,height/2,0)

this.arrivalX = map(this.to_long, -180,180,0,width)

this.arrivalY = map(this.to_lat, -90,90,height,height/2)

this.selected = function() {

if ( dist(mouseX, mouseY, this.departureX, this.departureY) < 10 ) {

return true

} else {

return false

}

}

this.drawDepartureAirport = function() {

if ( this.selected() ) {

fill(255,0,0,25)

} else {

fill(0,0,255,10)

}

ellipse(this.departureX, this.departureY, 5,5)

}

this.drawArrivalAirport = function() {

if ( this.selected() ) {

fill(255,0,0,25)

} else {

fill(0,0,255,1)

}

ellipse(this.arrivalX, this.arrivalY, 5,5)

}

this.drawAirports = function() {

this.drawDepartureAirport()

this.drawArrivalAirport()

}

}

function preload() {

table = loadTable("flights.csv","csv","header")

}

function setup() {

createCanvas(800, 800);

noStroke()

noLoop()

var rows = table.getRows()

for ( var i in rows ) {

var from_airport = rows[i].getString("from_airport")

var from_city = rows[i].getString("from_city")

var from_country = rows[i].getString("from_country")

var from_long = rows[i].getNum("from_long")

var from_lat = rows[i].getNum("from_lat")

var to_airport = rows[i].getString("to_airport")

var to_city = rows[i].getString("to_city")

var to_country = rows[i].getString("to_country")

var to_long = rows[i].getNum("to_long")

var to_lat = rows[i].getNum("to_lat")

var airline = rows[i].getString("airline")

var airline_country = rows[i].getString("airline_country")

var distance = rows[i].getNum("distance")

var this_flight = new flight(distance, from_long, from_lat, to_long, to_lat, from_country, to_country)

flights.push(this_flight)

}

}

function draw() {

background(255,255,255)

for ( var i in flights ) {

flights[i].drawAirports()

}

}

function mouseMoved() {

redraw()

return false

}

Here’s the interactive version (move your mouse across the top picture):

Let’s see what changed compared to script 16:

- We changed the calculation of

arrivalXandarrivalYto useto_longandto_latinstead offrom_longandfrom_lat(lines 14 and 15). - We removed the instruction to draw an ellipse at position

(arrivalX,arrivalY)from thedrawDepartureAirport()function. - We created a new function

drawArrivalAirport()(lines 34 to 41). We also set the colour in this function to be very transparent (opacity set to1instead of10), so that it is more clear which of the airports is active. - We created a new function

drawAirports()(lines 42 to 45), which basically just calls thedrawDepartureAirport()anddrawArrivalAirport()functions. - In the

draw()function, we replaceflight.drawDepartureAirport()withflight.drawAirports()so that both plots are made.

The resulting figure should look like this (without the annotated text):

Figure 13 - Brushing and linking between departure and arrival airports

Speeding things up: only drawing what needs to be drawn

In the example above, every time we move the mouse we draw all airports: the ones that are not selected in blue and the ones that are in red. Obviously it takes time to draw all those blue points even if they don’t change. But there is a better way: drawing to buffer. The main idea here is to draw all airports to an offline image that can be loaded quickly. Every time the user moves the mouse that image is just displayed (and not all airports have to be drawn separately again), and only the selected airports are drawn. The function to be used is createGraphics. So:

- In the

setup()function: create an image (technically a P5.Renderer object) by looping over all datapoints - In the

draw()function: load the image, and if necessary draw other things on top

What it looks like in code (script 18):

Script 18

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

var table;

var flights = [];

var pg

var flight = function(d,flo,fla,tlo,tla,fc,tc) {

this.distance = d

this.from_long = flo

this.from_lat = fla

this.to_long = tlo

this.to_lat = tla

this.from_country = fc

this.to_country = tc

this.departureX = map(this.from_long, -180,180,0,width)

this.departureY = map(this.from_lat, -90,90,height/2,0)

this.arrivalX = map(this.to_long, -180,180,0,width)

this.arrivalY = map(this.to_lat, -90,90,height,height/2)

this.selected = function() {

if ( dist(mouseX, mouseY, this.departureX, this.departureY) < 10 ) {

return true

} else {

return false

}

}

this.drawBackgroundAirport = function() {

pg.ellipse(this.departureX, this.departureY, 5,5)

pg.ellipse(this.arrivalX, this.arrivalY, 5,5)

}

this.drawSelectedAirport = function() {

if ( this.selected() ) {

fill(255,0,0,25)

ellipse(this.departureX, this.departureY, 5,5)

ellipse(this.arrivalX, this.arrivalY, 5,5)

}

}

}

function preload() {

table = loadTable("flights.csv","csv","header")

}

function setup() {

createCanvas(800, 800);

noStroke()

noLoop()

var rows = table.getRows()

for ( var i in rows ) {

var from_airport = rows[i].getString("from_airport")

var from_city = rows[i].getString("from_city")

var from_country = rows[i].getString("from_country")

var from_long = rows[i].getNum("from_long")

var from_lat = rows[i].getNum("from_lat")

var to_airport = rows[i].getString("to_airport")

var to_city = rows[i].getString("to_city")

var to_country = rows[i].getString("to_country")

var to_long = rows[i].getNum("to_long")

var to_lat = rows[i].getNum("to_lat")

var airline = rows[i].getString("airline")

var airline_country = rows[i].getString("airline_country")

var distance = rows[i].getNum("distance")

var this_flight = new flight(distance, from_long, from_lat, to_long, to_lat, from_country, to_country)

flights.push(this_flight)

}

pg = createGraphics(800,800);

pg.background(255,255,255);

pg.noStroke();

pg.fill(0,0,0,1);

for ( var i in flights ) {

flights[i].drawBackgroundAirport()

}

}

function draw() {

background(255,255,255)

image(pg,0,0)

for ( var i in flights ) {

flights[i].drawSelectedAirport()

}

}

function mouseMoved() {

redraw()

}

The interactive version:

Whereto from here?

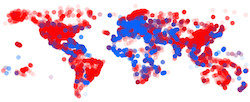

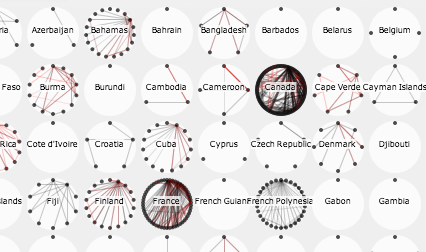

There are many different ways to show this information. This exact same dataset was visualized by Till Nagel during the visualization challenge in 2012 from visualising.org. Part of his entry is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14 - Entry by Till Nagel

Till focused on domestic flights, and wanted to show how many of these are served by domestic airlines or by foreign airlines.

Also have a look at Aaron Koblin’s visualization of flight patterns at http://www.aaronkoblin.com/work/flightpatterns/.

Exercise

- Alter the script to map other data attributes to these visuals. Can you find new insights?

- What other ways of visualizing this data could you think of?